A Peruvian Travelogue with Culture Smart! author John Forrest

The indigenous inhabitant’s of Peru’s Amazonian region number over one million today. Made up of 65 different ethnic groups and over a dozen linguistic families, there is great variety to be found in this part of the world.

While development continues throughout Peru, there still remains three areas along the border with Brazil where indigenous groups continue to live in isolation from broader society and the Western world.

One of such area is in Madre de Dios, one of the most ethnically diverse regions in the whole of Amazonia in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Here, small groups of Mashco-Piro are occasionally sighted along the Manu and Las Piedras rivers. Photographic evidence suggests that they still live as they have done traditionally for millennia.

There are an increasing number of small communities in the Peruvian Amazon, including Madre de Dios, offering tourist experiences. Most are run by long-term colonists who have often acquired substantial local knowledge. However, a few indigenous run casas de hospedaje (lodging houses) are beginning to appear where visitors can have a more authentic rainforest experience.

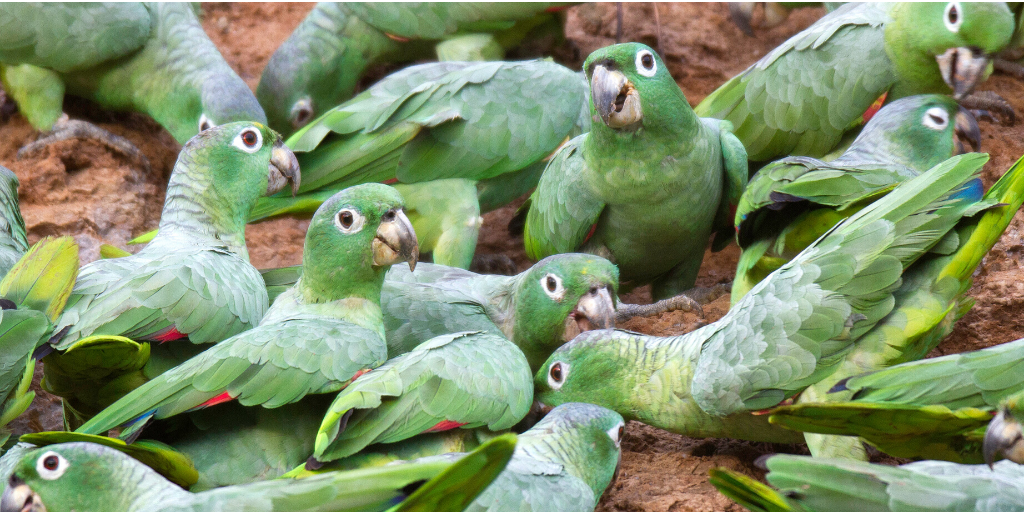

Tambopata, with world records for bird and butterfly species is one such area. Lodges and communities are accessed through the small, friendly, frontier city of Puerto Maldonado, just a 30-minute flight from Cusco.

We spent a few days staying in the Ese’eja community of Infierno (‘Hell’ – so named by early colonists due to the abundance of flies!), an hour up the Tambopata river. The once semi-nomadic Ese’eja have lived for centuries in the rainforest along the modern day Peru/Bolivia frontier. They now reside in three communities though larger numbers can be found over the border, in Bolivia.

Arriving in the afternoon, our guide took us down to a large river bank pool. We began by mashing up some barbasco roots with a riverbed stone and then threw the mash in to the centre of the large pool. Within seconds the surface was covered with fish of various sizes and colours: bluish, yellowish, pinkish, …. all gasping for air. We waded in and scooped up five large specimens in to our nets. Then we waited. Within half an hour, the smaller fish gradually recovered and disappeared back in to the murky depths of the pool the effect of the ‘poison’ having worn off.

Back at the village, we opened up the fish, gutted and smoked them over an open fire. From a huge cauldron an endless supply of boiled camote (sweet potato), plantain and yucca (cassava) were handed out and a bowl of spicy chilli sauce passed around to accompany the succulent fish.

That night, we slept in hammocks beneath thousands of woven palm leaves which formed the steep pitched roof of the maloca (traditional long house). A torrential downpour accompanied by thunder and lightning woke us in the middle of the night but by 6 a.m. the sun was up and moisture was already steaming from the surrounding vegetation.

We bathed in the shallows of a fine sandy beach once the locals had checked for evidence of caimans and half-buried rays. After a breakfast of maize porridge and bananas we entered the surrounding humid and dank forest, accompanied by an all-enveloping smell of decay.

Our indigenous guide was a fountain of knowledge, especially in plant identification and their potential medicinal uses. After he highlighted the merits of arco sacha leaves, I quickly grabbed a handful and rubbed them on my festering bites – within an hour days of irritation had subsided. When a large liana jungle vine blocked our path, our guide cut a metre-long section out of it with his machete and we drank the cool, fresh water stored inside.

Our indigenous guide was a fountain of knowledge, especially in plant identification and their potential medicinal uses. After he highlighted the merits of arco sacha leaves, I quickly grabbed a handful and rubbed them on my festering bites – within an hour days of irritation had subsided. When a large liana jungle vine blocked our path, our guide cut a metre-long section out of it with his machete and we drank the cool, fresh water stored inside.

However, we were much less willing to consume the large grubs that he enthusiastically gathered from within the trunk of a fallen palm tree, or the edible fungus off a rotting branch. Howler monkeys called in the distance, macaws screeched overhead and every so often something rustled in the undergrowth nearby but actual sightings, as if often the case, were few.

At a small cocha (an old oxbow lake) we dangled string with a small piece of meat tied to the end in the water in the hope that a piranha would bite, but in that cocha all the piranha must have been vegetarian. On our way back we passed through a traditional garden integrating crops, fruit trees, palms and medicinal plants.

The next day we arose at dawn to help bring in the rice harvest. A wild species planted in the garden was now ripe, the golden panicles standing a metre tall. During a long morning we harvested the panicles and filled our sacks with them before they were carried back to the village. There, the sacks were emptied out on a plastic sheet spread across a maloca floor. To the sounds of salsa music blaring out from a music system, we threshed the rice grains from the panicles by walking, treading and dancing across them. Once the grains had been separated, they were collected up and bagged.

Most experiences also touch on the many threats to the forest in the area such as gold-mining, which has devastated large areas on the Cusco road; small-scale farming, which accounts for the majority of the clearances; ranching, which replaces the enormously diverse forest with a mono-culture; and logging, though most of the valuable species, such as mahogany, are sadly long gone.

Accessible communities, such as the Infierno, are experiencing rapid change as contact with the outside world and Western society increases. Today, most dress in shorts and T-shirts, own mobile phones, use the internet and ride motorbikes around town. Urban areas present many attractions for the younger generations, challenging their retention of traditional knowledge and customs, much of which can only be passed down orally by community elders.

To read more about the culture of Peru and its people, you can buy the full guide from our shop here.