The vibrancy and electricity of this Monday at midnight made an English Friday night look bland by comparison.

The vibrancy and electricity of this Monday at midnight made an English Friday night look bland by comparison.

In an account of my relocation to Montpellier in the South of France, I tackle everything from first encounters to feminism on the other side of the Channel.

Top tip number 1 for moving abroad: When arriving alone, at midnight, with three suitcases, DO check which Hotel Ibis your reservation is at before you land.

Yes, that’s right, my first glimpses of my home-to-be were suitcase laden and tinged with exhaustion and confusion. Four (yes, four) hotel reception desks later, I sank down onto the bed and let my first half an hour in Montpellier sink in. The central (and architecturally stunning) Place de la Comédie had been shinning with lights, buzzing with locals, and brimming with the sound of music from street performers that surrounded the central fountain. The vibrancy and electricity of this Monday at midnight made an English Friday night look bland by comparison. The French people’s passion for socialising, food and drink is not exactly a secret, but the obvious effect that this had on supporting local and independent business and creating a healthy social dynamic between family and friends was immediately evident in the chattering square that evening. Perhaps this stark difference from the average British Monday night should have been a warning sign for greater contrasts to materialise.

Having studied French for over a decade and having travelled on my own from a young age, I had been dangerously naïve about the challenges that I would face by relocating. I had been to France dozens of times, worked briefly in Brittany and ordered more Alpine Tartiflette than most French Nationals. A nagging voice in my head told me that anywhere I could reach on the train couldn’t be THAT different, but the harsh reality was a dizzying combination of culture shock, homesickness and a raging desire for a Dairy Milk. I knew that I had to get out of my temporary accommodation and lay down some permanent roots but I was soon to learn that our geographical neighbours lived in a cultural world of their own.

Let’s start with the basics. In France, customer service refers to the general expectation that one should NEVER enter a place of work without a “Bonjour Monsieur/ Madame” and kissing twice (or three times in Montpellier). In return, you can expect a “customer is always wrong” attitude or at best, silence. There’s no way of avoiding this, take it with a pinch of salt and don’t skimp on the common courtesies that the French expect (occasionally it is also quite enjoyable to be the most enthusiastic customer possible in the face of blatant bluntness). Besides, in your average French shop or restaurant, while the customer experience might be compromised, the final product received is normally one of impeccable standard.

The French love of a National Holiday paves the way for stronger family connections and greater community spirit as households everywhere pour out onto the streets to spend time with one another.

The French love of a National Holiday paves the way for stronger family connections and greater community spirit as households everywhere pour out onto the streets to spend time with one another.

Even once you’ve mastered the procession of politesse that precedes interactions in France, moving abroad can be a long procession of vicious circles. You can’t set up a bank account without a permanent address, but you can’t register for an apartment without a bank account. If you want a phone contract, you’re going to need both of the above, but your average estate agent is unlikely to pick up the phone to a +44 dialling code. Approaching any of these tasks is also made considerably more challenging by the existing preference of hand written letters for official documentation, as well as the Mediterranean approach to opening hours. Assume that everything is closed on a Sunday and all banks are closed for the weekend and Monday; if you are eating lunch, most shopkeepers probably are too, and almost everything is closed in August as business owners venture off on their own holidays. I think as a Northern European, this relaxed approach to life is seen as somewhat idyllic: the ideal work-life balance that we compromise in place of absolute efficiency. However, the reality for homeless and penniless me was uncontrollable frustration. The key to succeeding in this environment is proper planning and preparation. Keep track of unexpected public holidays, consider that if you are paid on a Friday, your salary won’t hit your account until at least Tuesday, and stock up on Saturday morning for the weekend’s meals. In addition, the French love of a National Holiday, whilst inconvenient to the lonely traveller in need of a bank account, also paves the way for stronger family connections and greater community spirit as households everywhere pour out onto the streets to spend time with one another.

After a few weeks, these routines became second nature but other cultural aspects still remain a bitter pill to swallow. To be honest, as a millennial growing up in the UK, most aspects of gender inequality have barely touched my consciousness: 50p an hour less pay than an equally qualified male colleague that was rectified as soon as I pointed it out; the British man in white van honking his horn, or a couple of unwanted stares in the gym. It had never struck me that any country in modern Europe would be any different until I entered France.

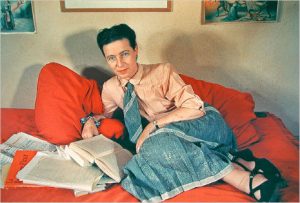

France is the nation that brought the world Simone de Beauvoir and I was wholly unprepared for the realities of feminism in France.

France is the nation that brought the world Simone de Beauvoir and I was wholly unprepared for the realities of feminism in France.

Some of my experience can be attributed to the fact that I was, for the first time, being introduced to values and attitudes apart from those of my own European (and Persian) heritage . In the Languedoc-Roussillon region, immigration from North Africa sits at 7% above the national average and, despite ambitious integration policies, many end up forming their own communities within France. Walking through one of these areas in the early afternoon, I was approached by a man who came up and stroked my blonde hair. I was beyond intimidated, pulled away, and literally ran to my house viewing. Here, the estate agent told me that “I was a pretty girl, and that was what pretty girls got”. It was later explained to me by a colleague that blonde hair was seen as something exceptionally rare and beautiful in North African culture and that it was not maliciousness, but genuine wonder that had provoked this man’s actions. Having since travelled to North Africa, I can confirm that despite general stereotyping, most locals have no ulterior motives beneath their gestures of kindness and flattery. In fact, after accepting this fact, I can honestly say that I have never experienced such hospitality and generosity as I have in rural Morocco. This behaviour was not, however, an isolated incident and I soon fell prey to male French nationals and their sultry “bonsoirs,” overbearing presence in bars, and one gentleman who cut me up twice on an evening run before following me to my door.

I thought that behaviour like this in white, middle class, European men was a thing of centuries gone by and research into the topic only served to further dishearten me. Despite equality laws passed in the 70s, women earn only 82% of their male counterparts and two out of three women earn minimum wage. There is a distinct lack of female representation in politics as the majority of politicians are drawn from Les Grandes Ecoles which have very few female attendees. Office dress codes for women still generally require elegant dress with heals and the French tend to be amongst the most appearance conscious females in Europe. In return, they are admired and adored, but this notion of chivalry seems far from 21st Century ideals. This fine exchange of exploitation and admiration is so widely accepted in the French workplace and home that it cannot truly be referred to as sexism, but a representation of a distinctly gendered society where men also have a role to play (as an outsider, that role seems to be something like the lead male in a black and white Rom-Com). I also think it is interesting to consider the place that language has in influencing gender types. To what extent can a society ever truly liberate itself from the restraints of defined gender roles when every noun is labelled as either masculine or feminine. Looking to the future, I wonder how the systems of the many gendered languages will develop and evolve to consider that not even humans have to define themselves as masculine or feminine in today’s world.

Men also have a role to play (as an outsider, that role seems to be something like the lead male in a black and white Rom-Com).

Men also have a role to play (as an outsider, that role seems to be something like the lead male in a black and white Rom-Com).

France is the nation that brought the world Simone de Beauvoir and I was wholly unprepared for the realities of feminism in France. There is no way that prior preparation can change the impact that this has on one’s sense of dignity in the workplace and wider community. I began by returning the unwanted “bonsoirs” with poorly constructed feminist rants. On another occasion, when an angry and frankly chauvinistic client demanded to speak to my boss (with the male prefix presumptuously used), I replied “certainly, but she is also a woman. You might speak to her supervisor but he is also incapable of completing a bank transfer on a Monday in France.” I received some French-sounding spluttering from the other end of the line and politely asked him to call back the following day when the banks had reopened.

The reality is that as a traveller, it is not my right to change these attitudes. The French are well known for their genuine pride in “being French” and this does still extend to notions of gallantry and chivalry both on the streets and in the workplace. The government have extended maternity benefits and access to childcare, and women are starting to enter middle-management, tending to marry and have children later. My own boss was a woman, highly respected in her industry and in no way willing to play her part in the gender roles that I have described here. The reality is that these attitudes are in decline and my experiences as documented here are no longer universal; I am certain that real change is coming. As with my early experience of my hair being touched by a stranger, I have learnt that thriving in a society that appears to be so backwards in terms of equality is all about understanding the roots of their attitudes. Yes, being pursued to my door was certainly a step too far, but the greetings that I often saw as demeaning or sleazy were largely just an example of the French man also playing along to what he saw as his role in society. My experience has also taught me that moving abroad is so much more than the practical matters of speaking the language and understanding the geography. It is about having an intrinsic understanding for the culture and learning to respect it, even if you do not entirely agree with it.

Planning a trip to France? Avoid any cultural faux pas and learn more about societal attitudes before you travel with Culture Smart.